Jeremy Grantham Explains How To

"Survive Betting Against Bull Market Irrationality"

Submitted by Tyler Durden

on 04/18/2012

http://albertpeia.com/grantham.htm

Ridiculous

as our market volatility might seem to an intelligent Martian, it is our

reality and everyone loves to trot out the “quote” attributed to Keynes (but

never documented): “The market can stay irrational longer than

the investor can stay solvent.” For us agents, he might better have said “The

market can stay irrational longer than the client can stay patient.”

Jeremy

Grantham

As

one may have guessed by now, the topic of this post will be Jeremy Grantham's

much anticipated quarterly letter, titled "The Tension between Protecting

Your Job or Your Clients’ Money" - a topic very germane to most asset

managers, who according to Grantham, engage not so much in alpha discovery (or

even pursuing levered beta), as much as preserving their careers, and in the

process succumbing to the one fundamental flaw of finance- herding. But don't worry: everyone

else does it too. Which is precisely what makes it so

attractive. After all, if everyone underperforms, nobody stands out, and

vice versa, which is why for every manager who succeeds and becomes a

billionaire, there are 999 others who try to break away from the herd, blow up

and are never heard of (pardon the pun) again, thank you survivorship bias. It

is this tension between the draw for riches and the probability of flaming out

on one hand, and the slow steady grind, associated with being a member of the

"flock" that more than anything, is at the

true heart of modern capital (mis)allocation

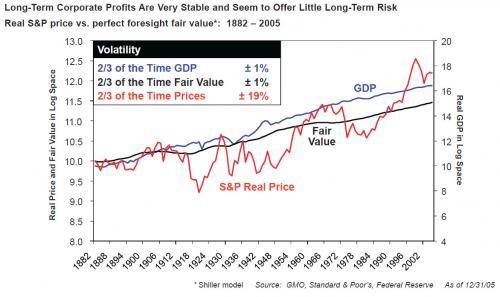

decisions. And it is because precisely of this herding effect that stock prices

end up whiplashed around fair value by a margin of ±19% two-thirds of the time,

even as GDP and fair values moves at a glacial ±1 pace. Call it momo, call it "safety in numbers", it's real name is irrationality.

It is precisely this irrationality that Keynes had in mind when he may or may

not have uttered his infamous quote.

This

is how Grantham puts it.

The

central truth of the investment business is that investment behavior is driven

by career risk. In the professional investment business we are all agents,

managing other peoples’ money. The prime directive, as Keynes knew so well, is

first and last to keep your job. To do this, he explained that you must never,

ever be wrong on your own. To prevent this calamity, professional investors pay

ruthless attention to what other investors in general are doing. The great majority “go with the flow,” either

completely or partially. This creates herding, or momentum,

which drives prices far above or far below fair price. There are many other ineffi ciencies in market

pricing, but this is by far the largest. It explains the discrepancy between a

remarkably volatile stock market and a remarkably stable GDP growth, together

with an equally stable growth in “fair value” for the stock market. This

difference is massive – two-thirds of the time annual GDP growth and annual

change in the fair value of the market is within plus or minus a tiny 1% of its

long-term trend as shown in Exhibit 1.

The

market’s actual price – brought to us by the workings of wild and wooly

individuals – is within plus or minus

19% two-thirds of the time. Thus, the market moves 19 times more than is justifi ed

by the underlying engines! This incredible demonstration of the

behavioral dominating the rational and the “efficient” was first noticed by

Robert Shiller over 20 years ago and was countered by

some of the most tortured logic that the rational expectations crowd could

offer, which is a very high hurdle indeed. Shiller’s

“fair value” for this purpose used clairvoyance. He “knew” the future flight

path of all future dividends, from each starting position of 1917, 1961, and

all the way forward. The resulting theoretical value was always stable (it

barely twitched even in the Great Depression), but this data was widely ignored

as irrelevant. And ignoring it may be the correct response on the part of most

market players, for ignoring the volatile up-and-down market moves and

attempting to focus on the slower burning long-term reality is simply too

dangerous in career terms. Missing a

big move, however unjustified it may be by fundamentals, is to take a very high

risk of being fired. Career risk and the resulting herding it

creates are likely to always dominate investing. The short term will always be

exaggerated, and the fact that a corporation’s future value stretches far into

the future will be ignored. As GMO’s Ben Inker has

written, two-thirds of all corporate value lies out beyond 20 years. Yet the

market often trades as if all value lies within the next 5 years, and sometimes

5 months.

Since

in our day and age, the only way to generate wealth is to manage asset, not to

collect wages (as everyone's favorite peak Marxism chart has shown over and

over), everyone is now an fund manager. Which means that the above observations have to be put in the

context of managing one's portfolio. Grantham does that next, and this

is the part that the hedge funders, those so terrified to fight the Fed, and

thus shivering in groups of like-minded momentum chasers, should pay attention

to:

Ridiculous

as our market volatility might seem to an intelligent Martian, it is our

reality and everyone loves to trot out the “quote” attributed to Keynes (but

never documented): “The market can stay

irrational longer than the investor can stay solvent.” For us

agents, he might better have said “The

market can stay irrational longer than the client can stay patient.”

Over the years, our estimate of “standard client patience time,” to coin a

phrase, has been 3.0 years in normal conditions. Patience can be up to a year

shorter than that in extreme cases where relationships and the timing of their

start-ups have proven to be unfortunate. For example, 2.5 years of bad

performance after 5 good ones is usually tolerable, but 2.5 bad years from

start-up, even though your previous 5 good years are wellknown but helped someone else, is absolutely not the

same thing! With good luck on starting time, good personal relationships, and

decent relative performance, a client’s patience can be a year longer than 3.0

years, or even 2 years longer in exceptional cases. I like to say that good

client management is about earning your fi rm an incremental year of patience. The extra year is very

important with any investment product, but in asset allocation, where mistakes

are obvious, it is absolutely huge and usually enough

So is

there any hope for those who wish to break the mold, fight the Fed, and be

contrarians for the sake of reality, and, well, because sometime it is just

much more fun to tell the lemmings the cliff ended 10 feet ago. Why, yes

You

apparently can survive betting against bull market irrationality if you meet

three conditions. First,

you must allow a generous Ben

Graham-like “margin of safety” and wait for a real outlier before you make a

big bet. Second, you

must try to stay reasonably diversified. Third, you must never use

leverage. In my personal opinion (and with the benefit of

hindsight, you might add), although we in asset allocation felt exceptionally

and painfully patient at the time, we did not in

the past always hold our fire long enough or be patient enough. It is the

classic failing of value managers (and poker players for that matter) to get

impatient and bet too hard too soon. In addition, GMO was not always optimally

diversified. We are generally more cautious (or, if you prefer, “more

experienced”) now than in 1998 with respect to, for example, both patience and

diversification, and at least we in asset allocation always stayed away from

leverage. The

Yet

even so, doing the right thing is often precluded by one's career limitations:

This

exemplifies perfectly Warren Buffett’s adage that investing is simple but not

easy. It is simple to see what is necessary, but not easy to be willing or able

to do it. To repeat an old story: in 1998 and 1999 I got about 1100 fulltime

equity professionals to vote on two questions. Each and every one agreed that

if the P/E on the S&P were to go back to 17 times earnings from its level

then of 28 to 35 times, it would guarantee a major bear market. Much more

remarkably, only 7 voted that it would not go back! Thus, more than 99% of the

analysts and portfolio managers of the great, and the not so great, investment

houses believed that there would indeed be “a major bear market” even as their

spokespeople, with a handful of honorable exceptions, reassured clients that

there was no need to worry.

Career

and business risk is not at all evenly spread across all investment levels.

Career risk is very modest, for example, when you are picking insurance stocks;

it is therefore hard to lose your job. It will usually take 4 or 5 years before

it becomes reasonably clear that your selections are far from stellar and by

then, with any luck, the research director will have changed once or twice and

your defi ciencies will

have been lost in history. Picking oil, say, versus insurance is much more

visible and therefore more dangerous. Picking cash or “conservatism” against a

roaring bull market probably lies beyond the pain threshold of any publicly

traded enterprise. It simply cannot take the risk of being seen to be “wrong”

about the big picture for 2 or 3 years, along

with the associated loss of business. Remember, expensive

markets can continue on to become obscenely expensive 2 or 3 years later, as

As

usual, terrific advice from one of the few people out there who still gets it. Much more in the full letter below (pdf link)