Obama's grandfather tortured by the British? A fantasy (like

most of the President’s own memoir)

By Toby

Harnden

PUBLISHED:| UPDATED:

‘A new biography of Barack Obama has established that his

grandfather was not, as is related in the President’s own memoir, detained by

the British in Kenya and found that claims that he was tortured were a

fabrication.

'Barack Obama: The Story' by David Maraniss

catalogues dozens of instances in which Obama deviated significantly from the

truth in his book 'Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance'. The

641-page book punctures the carefully-crafted narrative of Obama’s life.

One of the enduring myths of Obama’s ancestry is that his

paternal grandfather Hussein Onyango Obama, who

served as a cook in the British Army, was imprisoned in 1949 by the British for

helping the anti-colonial Mau Mau rebels and held for

several months.

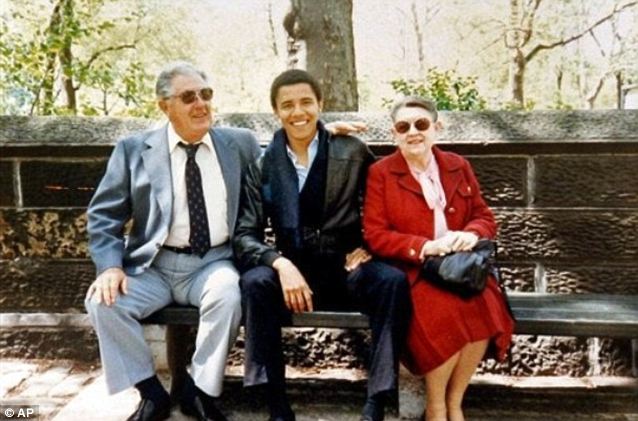

Family

tree: Barack Obama (centre) with his maternal grandparents

Obama’s step-grandmother Sarah, Onyango

wife, who is still living, is quoted in the future President’s memoir, as

saying: ‘One day, the white man’s askaris came to

take Onyango away, and he was placed in a detention

camp.

More...

‘But he had been in the camp for over six months,

and when he returned to Alego he was very thin and

dirty. He had difficulty walking, and his head was full of lice. He was so

ashamed, he refused to enter his house or tell us what happened.’

In a 2008 interview, Sarah Obama claimed that he was

‘whipped every morning and evening’ by the British. ‘They would sometimes

squeeze his testicles with metal rods. They also pierced his nails and buttocks

with a sharp pin, with his hands and legs tied together. He was lucky to

survive. Some of his fellow inmates were mutilated with castration pliers and

beaten to death with clubs.’

But Maraniss, who researched

Obama’s life in Kenya, Indonesia, Hawaii and the mainland United States, found

that there were ‘no remaining records of any detention, imprisonment, or trial

of Hussein Onyango Obama’. He interviewed five people

who knew Obama’s grandfather, who died in 1979, who ‘doubted the story or were

certain it did not happen’.

Fabricated?: 'Barack Obama: The Story' by David Maraniss

catalogues dozens of instances in which Obama deviated significantly from the

truth in his book

This undermines the received wisdom that Obama’s grandfather

was a victim of oppression, an assumption that has in turn fuelled theories

that Obama harbours an animus towards

John Ndalo Aguk,

who worked with Onyango before the alleged

imprisonment and was in touch with him weekly afterwards said he 'knew nothing'

about any detention and would have noticed if he had gone missing for several

months.

Zablon Okatch, who worked with Onyango

as a servant to American diplomats after the supposed incarceration, said:

‘Hussein was never jailed. I know that for a fact. It would have been difficult

for him to get a job with a white family, let alone a diplomat, if he once

served in jail.’

Charles Oluoch, whose father was

adopted by Onyango, said that ‘he did not have any

trouble with the government in any way'.

Dick Opar, a relative by marriage

to Onyango and a senior Kenyan police official, gave

what Maraniss judged to be the most authoritative

word. ‘People make up stories,’ he said. ‘If you get arrested, you say it was

the fight for independence, but they are arrested for another thing.

‘I would have known. I would have known. If he was in Kamiti Prison for only a day, even if for a day, I would

have known.’

Maraniss also casts a sceptical eye on Obama’s

grandmother’s tales of racism in Kansas, doubting whether she was ever

chastised for addressing a black janitor as ‘Mister’ or ridiculed for playing

with a black girl.

Obama himself, Maraniss finds,

deliberately distorted elements of his own life to fit into a racial narrative.

The author writes that Obama presents himself in his memoir as ‘blacker and

more disaffected’ than he really was.

The memoir ‘accentuates characters drawn from black

acquaintances who played lesser roles his real life but could be used to

advance a line of thought, while leaving out or distorting the actions of

friends who happened to be white’.

Researched:

David Maraniss (left) found that there were 'no remaining

records of any detention, imprisonment, or trial of Hussein Onyango

Obama', the President's grandfather

In the forward to his memoir, Obama wrote that ‘for the sake

of compression, some of the characters that appear are composites of people

I’ve known, and some events appear out of precise chronology’.

But Maraniss writes that Obama’s

book is ‘literature and memoir, not history and autobiography’ and concludes:

‘The character creations and rearrangements of the book are not merely a matter

of style, devices of compression, but are also substantive.’

Writing about his schooldays, Obama created a friend called

Maraniss found, however, that Regina was based on Caroline Boss, a white student

leader at

The book also notes that Obama removed two white roommates

in

A tale of the father of Obama’s Indonesian stepfather Soewarno Martodihardjo being

killed by Dutch soldiers as he fought for Indonesian independence turns out to

be ‘a concocted myth in almost all respects’, Maraniss

finds.

According to the book, both Obama’s father and his paternal

grandfather were abusive towards women and Maraniss

finds that Obama’s story that he was abandoned by his father when he was two

was false – in fact, Obama’s mother fled to Washington state a year earlier,

possibly because she was being beaten.

A character in Obama’s memoir called Ray, portrayed as a

symbol of young blackness, is in fact based on a fellow pupil who was half

Japanese, part native American and part black and was

not a close friend.

‘In the memoir Barry and Ray, could be heard complaining

about how rich white haole [upper class white

Hawaiian] girls would never date them. In fact, neither had

much trouble in that regard.’

Obama notes of his own grandfather that he was apt to create

‘history to conform with the image he wished for

himself’.

Maraniss, who also wrote an acclaimed biography of Bill Clinton, suggests that

throughout his life Obama himself, following on from his forbears on both

sides, has done the same thing.’