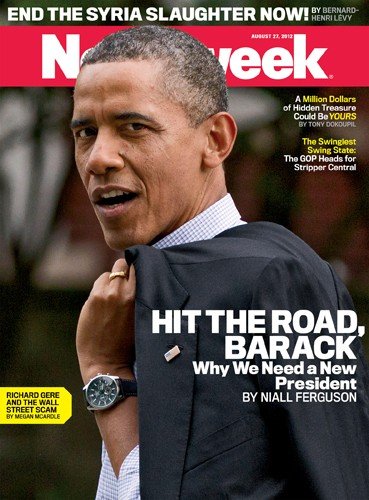

Niall Ferguson: Obama’s

Gotta Go

‘Why

does Paul Ryan scare the president so much? Because Obama has broken his

promises, and it’s clear that the GOP ticket’s path to prosperity is our only

hope.

I was a good loser four years ago. “In the grand

scheme of history,” I wrote the day after Barack Obama’s election as president,

“four decades is not an especially long time. Yet in that brief period

Yet the question confronting the country

nearly four years later is not who was the better candidate four years ago. It

is whether the winner has delivered on his promises. And the sad truth is that

he has not.

In his inaugural address, Obama

promised “not only to create new jobs, but to lay a new foundation for growth.”

He promised to “build the roads and bridges, the electric grids, and digital

lines that feed our commerce and bind us together.” He promised to “restore

science to its rightful place and wield technology’s wonders to raise health

care’s quality and lower its cost.” And he promised to “transform our schools

and colleges and universities to meet the demands of a new age.” Unfortunately

the president’s scorecard on every single one of those bold pledges is pitiful.

COVER STORY: Obama has broken

his promises, and it's clear that the GOP ticket's path to prosperity is our

only hope bit.ly/QQLouG

In an unguarded moment earlier this

year, the president commented that the private sector of the economy was “doing

fine.” Certainly, the stock market is well up (by 74 percent) relative to the

close on Inauguration Day 2009. But the total number of private-sector jobs is

still 4.3 million below the January 2008 peak. Meanwhile, since 2008, a

staggering 3.6 million Americans have been added to Social Security’s

disability insurance program. This is one of many ways unemployment is being

concealed.

In his fiscal year 2010 budget—the

first he presented—the president envisaged growth of 3.2 percent in 2010, 4.0

percent in 2011, 4.6 percent in 2012. The actual numbers were 2.4 percent in

2010 and 1.8 percent in 2011; few forecasters now expect it to be much above

2.3 percent this year.

Niall

Ferguson discusses Obama's broken promises on ‘Face the Nation.’

Unemployment was supposed to be 6

percent by now. It has averaged 8.2 percent this year so far. Meanwhile real

median annual household income has dropped more than 5 percent since June 2009.

Nearly 110 million individuals received a welfare benefit in 2011, mostly

Medicaid or food stamps.

Welcome to Obama’s

Not only did the initial fiscal

stimulus fade after the sugar rush of 2009, but the president has done

absolutely nothing to close the long-term gap between spending and revenue.

His much-vaunted health-care reform

will not prevent spending on health programs growing from more than 5 percent

of GDP today to almost 10 percent in 2037. Add the projected increase in the

costs of Social Security and you are looking at a total bill of 16 percent of

GDP 25 years from now. That is only slightly less than the average cost of all

federal programs and activities, apart from net interest payments, over the

past 40 years. Under this president’s policies, the debt is on course to

approach 200 percent of GDP in 2037—a mountain of debt that is bound to reduce

growth even further.

And even that figure understates the

real debt burden. The most recent estimate for the difference between the net

present value of federal government liabilities and the net present value of

future federal revenues—what economist Larry Kotlikoff

calls the true “fiscal gap”—is $222 trillion.

The president’s supporters will, of

course, say that the poor performance of the economy can’t be blamed on him.

They would rather finger his predecessor, or the economists he picked to advise

him, or Wall Street, or

There’s some truth in this. It was

pretty hard to foresee what was going to happen to the economy in the years

after 2008. Yet surely we can legitimately blame the president for the

political mistakes of the past four years. After all, it’s the president’s job

to run the executive branch effectively—to lead the nation. And here is where

his failure has been greatest.

Photos:

Obama Faces a Tough Crowd in Iowa

On paper it looked like an economics

dream team: Larry Summers, Christina Romer, and Austan Goolsbee, not to mention

Peter Orszag, Tim Geithner,

and Paul Volcker. The inside story, however, is that the president was wholly

unable to manage the mighty brains—and egos—he had assembled to advise him.

According to Ron Suskind’s

book Confidence Men, Summers told Orszag over dinner in May 2009: “You know, Peter, we’re

really home alone ... I mean it. We’re home alone. There’s no adult in charge.

This problem extended beyond the White

House. After the imperial presidency of the Bush era, there was something more

like parliamentary government in the first two years of Obama’s administration.

The president proposed; Congress disposed. It was Nancy Pelosi and her cohorts

who wrote the stimulus bill and made sure it was stuffed full of political

pork. And it was the Democrats in Congress—led by Christopher Dodd and Barney

Frank—who devised the 2,319-page Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

(Dodd-Frank, for short), a near-perfect example of excessive complexity in

regulation. The act requires that regulators create 243 rules, conduct 67

studies, and issue 22 periodic reports. It eliminates one regulator and creates

two new ones.

It is five years since the financial

crisis began, but the central problems—excessive financial concentration and

excessive financial leverage—have not been addressed.

Today a mere 10 too-big-to-fail

financial institutions are responsible for three quarters of total financial

assets under management in the

Ironically, the core Obamacare concept of the “individual mandate” (requiring

all Americans to buy insurance or face a fine) was something the president

himself had opposed when vying with Hillary Clinton for the Democratic

nomination. A much more accurate term would be “Pelosicare,”

since it was she who really forced the bill through Congress.

Pelosicare was not

only a political disaster. Polls consistently showed that only a minority of

the public liked the ACA, and it was the main reason why Republicans regained

control of the House in 2010. It was also another fiscal snafu. The president

pledged that health-care reform would not add a cent to the deficit. But the

CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation now estimate that the

insurance-coverage provisions of the ACA will have a net cost of close to $1.2

trillion over the 2012–22 period.

The president just kept ducking the

fiscal issue. Having set up a bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal

Responsibility and Reform, headed by retired Wyoming Republican senator Alan

Simpson and former Clinton chief of staff Erskine Bowles, Obama effectively

sidelined its recommendations of approximately $3 trillion in cuts and $1

trillion in added revenues over the coming decade. As a result there was no

“grand bargain” with the House Republicans—which means that, barring some

miracle, the country will hit a fiscal cliff on Jan. 1 as the Bush tax cuts

expire and the first of $1.2 trillion of automatic, across-the-board spending

cuts are imposed. The CBO estimates the net effect could be a 4 percent

reduction in output.

The failures of leadership on economic

and fiscal policy over the past four years have had geopolitical consequences.

The World Bank expects the

Fact

Check: Has Obama Kept His Promises?

Meanwhile, the fiscal train wreck has

already initiated a process of steep cuts in the defense budget, at a time when

it is very far from clear that the world has become a safer place—least of all

in the Middle East.

For me the president’s greatest failure

has been not to think through the implications of these challenges to American

power. Far from developing a coherent strategy, he believed—perhaps encouraged

by the premature award of the Nobel Peace Prize—that all he needed to do was to

make touchy-feely speeches around the world explaining to foreigners that he

was not George W. Bush.

In Tokyo in November 2009, the

president gave his boilerplate hug-a-foreigner speech: “In an interconnected

world, power does not need to be a zero-sum game, and nations need not fear the

success of another ... The United States does not seek to contain China ... On

the contrary, the rise of a strong, prosperous China can be a source of strength

for the community of nations.” Yet by fall 2011, this approach had been

jettisoned in favor of a “pivot” back to the Pacific, including risible

deployments of troops to

His

In the case of

“This is what happens when you get

caught by surprise,” an anonymous American official told The New York Times

in February 2011. “We’ve had endless strategy sessions for the past two years

on Mideast peace, on containing

Remarkably the president polls

relatively strongly on national security. Yet the public mistakes his administration’s

astonishingly uninhibited use of political assassination for a coherent

strategy. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in

The real crime is that the

assassination program destroys potentially crucial intelligence (as well as

antagonizing locals) every time a drone strikes. It symbolizes the

administration’s decision to abandon counterinsurgency in favor of a narrow

counterterrorism. What that means in practice is the abandonment not only of

It is a sign of just how completely

Barack Obama has “lost his narrative” since getting elected that the best case

he has yet made for reelection is that Mitt Romney should not be president. In his

notorious “you didn’t build that” speech, Obama listed what he considers the

greatest achievements of big government: the Internet, the GI Bill, the Golden

Gate Bridge, the Hoover Dam, the Apollo moon landing, and even

(bizarrely) the creation of the middle class. Sadly, he couldn’t mention

anything comparable that his administration has achieved.

Now Obama is going head-to-head with

his nemesis: a politician who believes more in content than in form, more in

reform than in rhetoric. In the past days much has been written about Wisconsin

Congressman Paul Ryan, Mitt Romney’s choice of running mate. I know, like, and

admire Paul Ryan. For me, the point about him is simple. He is one of only a

handful of politicians in Washington who is truly sincere about addressing

this country’s fiscal crisis.

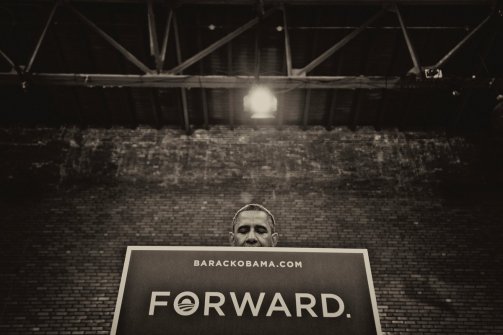

Want to discuss this week's cover

story? Use the hashtag #HitTheRoadBarack--just

as it appears on the cover.

Over the past few years Ryan’s “Path to Prosperity”

has evolved, but the essential points are clear: replace Medicare with a

voucher program for those now under 55 (not current or imminent

recipients), turn Medicaid and food stamps into block grants for the states,

and—crucially—simplify the tax code and lower tax rates to try to inject some

supply-side life back into the U.S. private sector. Ryan is not preaching

austerity. He is preaching growth. And though Reagan-era veterans like David

Stockman may have their doubts, they underestimate Ryan’s mastery of this

subject. There is literally no one in Washington who understands the challenges

of fiscal reform better.

Just as importantly, Ryan has learned

that politics is the art of the possible. There are parts of his plan that he

is understandably soft-pedaling right now—notably the new source of federal

revenue referred to in his 2010 “Roadmap for America’s Future” as a “business

consumption tax.” Stockman needs to remind himself that the real “fairy-tale

budget plans” have been the ones produced by the White House since 2009.

Photos:

Obama Faces a Tough Crowd in Iowa

I first met Paul Ryan in April 2010. I

had been invited to a dinner in

It remains to be seen if the American

public is ready to embrace the radical overhaul of the nation’s finances that

Ryan proposes. The public mood is deeply ambivalent. The president’s approval

rating is down to 49 percent. The

But one thing is clear. Ryan psychs Obama out. This

has been apparent ever since the White House went on the offensive against Ryan

in the spring of last year. And the reason he psychs

him out is that, unlike Obama, Ryan has a plan—as opposed to a narrative—for

this country.

Mitt Romney is not the best candidate

for the presidency I can imagine. But he was clearly the best of the Republican

contenders for the nomination. He brings to the presidency precisely the kind

of experience—both in the business world and in executive office—that Barack

Obama manifestly lacked four years ago. (If only Obama had worked at Bain

Capital for a few years, instead of as a community organizer in

The voters now face a stark choice.

They can let Barack Obama’s rambling, solipsistic narrative continue until they

find themselves living in some American version of Europe, with low growth,

high unemployment, even higher debt—and real geopolitical decline.

Or they can opt

for real change: the kind of change that will end four years of economic

underperformance, stop the terrifying accumulation of debt, and reestablish a

secure fiscal foundation for American national security.

I’ve said it before: it’s a choice

between les États Unis and the Republic of the

I was a good loser four years ago. But

this year, fired up by the rise of Ryan, I want badly to win.’